| General Meeting Reports for 2025 | Return to Index |

| Apr 2025 | An epic rock MAC gig |

On the April Meeting MAC members were treated

to an epic rock presentation at the Willis Room.

It was 'The Winter of Discontent', the opus

magnus of our esteemed Matt Jelicich and the

leader of a rock band, Danny Lopez. We also

enjoyed an accomplished choir comprised of four

ladies and four gentlemen. All presenters were

professional and very talented, but more on that

later...

As you may know, Matt was raised an only child

in the difficult period immediately after WWII.

Life was tough and driven by survival, and most

people of that time preferred a salaried, business

pathway. Raising and supporting his family took

centre stage and his "scribbling" (his term, not

mine) became a background indulgence.

During Covid, Matt quickly realised that much of

his earlier 'scribbling' related to the "new" Covid

world. He was motivated to complete a dark epic,

conveying his alarm of our world as it slipped into

pandemic, distorting our institutions, changing

our governance, stripping our freedom and

mental health. As a wordsmith Matt has a great

love of Leonard Cohen, and an awareness of the

dark aspects of the human condition. Our

resourceful Programme Co-ordinator, Dave

Polanske, encouraged him to present his work to

the Club.

The evening started with Matt introducing us

to his work, its origins, and a hint of its

meaning... he warmed up the audience very

well, but we did not glimpse the deep intent in

his lyrics and Danny's music.

The performance began with the full

ensemble of musicians and singers, a rock

ballad which warmed up the audience to the

"Winter of Discontent". It was followed by a

beautiful rendition of 'Duke of Earl', a wellknown

50s piece sung by an acapella with

four male members of the eight-member

choir. The third piece was with all the singers

gently backed by the band but lightly

amplified, and the sound was wonderfully

harmonising. It was very pleasing music,

harking back to a brighter era of the US. The

rendition showed the range and skill of the

four part Acapella and set the scene for an

abrupt mood change.

Next Danny, accomplished front man and

composer of the music, performed a short but

impressive guitar solo leading into "Winter of

Discontent". This broke the stillness with

Kane Skinner, the outstanding percussionist,

Jon Lambousis, the bass guitarist and the

eight-part choir. All instruments were

amplified, and the 'Winter of Discontent' was

very, very loud! The sound was redolent of

Jimi Hendrix; Danny is a wonderful rock

guitarist and vocalist. Matt's words were

displayed overhead via slide projector, so the

audience could see dramatic images and read

off the lyrics.

We might describe the 'Winter of Discontent' as

Rock. But with musical accompanist from Danny,

his musicians with some recorded backing and

words from Matt the situation transformed to a

hybrid of rock music, protest song, and classical

requiem. This most unusual work reminded me

of Pink Floyd's 1979 'The Wall', Barry McGuire's

1965 'Eve of Destruction', and Benjamin Britten's

1962 War Requiem (words from Wilfred Owen).

If that was Matt's intent, he certainly had our full

attention!

Knowing Matt, I was not surprised by the

darkness, energy and breadth of 'Winter of

Discontent'. It was shocking, dystopic, highenergy

and thought-provoking. In any

conversation with Matt, we are always impressed

with his sociable pessimism and his insightful

cynicism, and these traits were in full song in

'Winter of Discontent'. I came away somewhat

dispirited by his dystopian future where truth,

freedom and democracy are corrupted; musically

'Winter of Discontent' was fast-moving; a

magisterial, dramatic sound, a little discordant. It

was charged with startling lyrics, suited well for a

young generation, all the clearer for the lyrics and

captions projected on the screen at the meeting's

end. But philosophically the work reminded me

of Richard Strauss' 'Four Last Songs' written in

1947-8, a year before he died. Strauss paints a

picture of a dying civilisation and the effect is

profound emotionally. Matt's piece left me

with similar feelings; profound sadness and

the loss of great future.

Any piece of great art in any form should

leave us with a sense of wonder, and

sometimes with a sense of unease and even a

dark awareness of despair. Matt's words and

Danny's music achieved these emotions in

spades. We should be very grateful for Matt

and Danny and offer admiration that Matt

had the courage to create, produce and

commit his work to our Club; very few of us

would ever have the self-belief to present our

own artistic work. The 'Winter of Discontent'

was one of the presentations over almost

thirty years in the Club I will never forget.

For those who did not attend and/or those

who did but would like to revisit the finished

work at a volume level better suited to their

preference, here is the YouTube link:

https:// www.youtube.com/watch?v=6piuSYuTso0

Hugh Dean

Our March GM was presented by Toby Taylor of

JayVee Technologies and Geoff Haynes of Hey

Now Hi Fi. Toby brought along of electronics

from the Sound Performance Lab range driving a

pair of Revival Audio speakers. In the first half he

demonstrated a modestly priced streamer, around

$600, paired with one of their mid-priced

integrated amplifiers.

The demonstration,

together with a varied and interesting music

selection courtesy of Dave Polanske, gave a hint of

what the system could do but when the streamer

was substituted for a Mark Levinson turntable

and one of SPL's monoblocks the sound became

richer, possibly more valve like and definitely

more engaging.

During the second half Geoff showed off the

Kirmuss record cleaning system and was busy

cleaning and drying a dirty record several times to

demonstrate its effectiveness. Geoff played the

record for us, then completed 3 cycles of the

cleaning process, taking approximately 15

minutes. He then played it again.

To me the sonic

improvement of the before and after cleaning

process was quite noticeable, and most members

agreed it was very apparent. I think a lot of them

were surprised how effective this cleaning process

is. It showed the Kirmuss RCM is worth

considering as a means to get the most SQ from

your vinyl collection as well as reducing the

intrusion of clicks and pops during playback.

My sincere thanks to Toby and Geoff for their

time and effort spent on their presentation and

for providing us a great evening's entertainment.

Laurie Nicholson

Tim and Ric brought along an array of vintage

Williamson amplifiers (valve, of course) to

showcase the very great leap in practical

amplifier design that Theo Williamson, a

Scotsman, achieved in 1947. Tim and Ric's

exceptionally entertaining talk was peppered

with juicy morsels, including the cover of an

electronic magazine of the time nominating

the Williamson as "the amplifier to end

amplifiers" (how often have we heard that

claim made?) and a personal description of the

dubious joys of adjusting the bias of an old

valve amplifier when the adjustment

potentiometer was un-insulated and carried

400 VDC. The two amplifiers on

demonstration were fed by a very modern

Technics SL-G700M2 streamer provided by

the program co-ordinator, Dave Polanske.

Dave also provided the Leak sandwich

speakers, more of which anon.

In the days just before the meeting I had a

couple of colleagues ask me what I thought

about the impending demonstration. I

explained in broad terms the historical

significance of the Williamson amplifier and

the novel design of the Leak sandwich

speakers, and concluded by suggesting it could

be a very interesting session but that I was

afraid the system would struggle to fill the

Willis Room. After all, the Williamson

amplifier was rated at only something like

13-15 watts (on a good day, with a tailwind

and a downhill slope) and the Leak speakers,

despite being floor-standers, were likely quite

inefficient and probably themselves rated at

only 15- 20 watts. Having seem modern

transistor and Class D amplifiers with power

outputs that would rival those of a small

nuclear reactor struggle in the cavernous Willis

Room, I thought I had good reasons for some

trepidation as to how the system would cope.

How wrong I was! The system made

GLORIOUS music. (Note that I say 'music', not

'sound'.) Person after person I spoke to during

the evening and afterwards, on the weekend,

remarked on how magnificent the system

portrayed music. One member, who I would

describe as an ardent audiophile, said "They

aren't hi-fi but they make fabulous music".

Another, this time of more antiquated audio

and musical interests, reported the set-up had

among the best instrumental timbre he had

ever heard (and he owns a pair of QUAD 57s, so

that's quite some praise). He thought the

rendition of the Dean Martin track was

remarkable. I was won-over by the Elvis track

played just after the coffee break: had "Can't

help falling in love" (recorded in 1961 for Elvis'

1962 film Blue Hawaii - and in the film sung

not to his lover but to his grandmother!) ever

sounded so heart-felt, so emotive, so moving,

so musically correct?

So, what was the equipment responsible for

such unbridled pleasure? I'll start with the

speakers, as I have a long-standing personal

connection to the Leak sandwiches.

The Leak sandwich speaker saw the light of day

in 1961. It was called a 'sandwich' because the

speaker cone was a thin (2 mm?) layer of

expanded polystyrene foam sandwiched

between two very thin layers of aluminium foil.

The chassis was made of cast aluminium and

the surround was made from cambric fibre. The

bass driver was big at 13" and the cabinets

themselves were also substantial (60 L) and -

of course - finished in period-correct real

walnut or teak veneer with a thick cloth grille.

The tweeter was also a sandwich design, of 3"

diameter, and it crossed over to the woofer at

900 Hz. Since the speakers were designed to be

used with a valve amplifier, they had an

impedance of 15 ohms. I believe this initial,

large, floor-standing version was called the

Model 2060.

I was seriously mistaken when I hazarded to

guess that the system would be inadequate for

the Willis Room. The speakers must have been

far more efficient than I had guessed, as they

had no problem at all in filling the room. I

tried to find what their efficiency was via an

online search, but came up with nothing. I now

believe it must have been somewhere in the

mid-to-high 90s (i.e. dB/watt at 1 m; and

remember they were 15 ohm speakers). A very

harsh critic might say the top-end was rolled

off too - but what can you expect from a 3"

cone tweeter with what would now be

considered an impossibly heavy cone (i.e. it

wasn't built from no beryllium or titanium or

diamond wunder-material). In any case, it's

likely that few of our members can hear

beyond 10-12 kHz, so our hearing and not the

drive units is probably the limiting factor. And,

yes, the bass driver didn't plumb the depths

down to stygian, sub-sonic frequencies: who

cares? What the system did do magnificently

was portray voices, and particularly male

voices. Bravo. Was this because they were

being reproduced by a huge (13") woofer that

operated solo up to 900 Hz? Maybe.

The sight of these lovely floor-standing, realwood-

veneered creatures brought back a flood

of memories. About 25 years ago I owned a

near-mint pair of their smaller and younger

brothers, the Sandwich Model 200. They had a

smaller (8") sandwich-cone bass driver and

two purple (yes, purple!) 60 mm Mylar drive

units, one for the midrange and the other

acting as the tweeter. I drove them via a 1960s

Japanese amplifier that went by the name of

'Star' which, if recollection serves me correctly,

used four EL34 values in push-pull operation.

It made a lovely, warm, comfortable sound,

perfect for my office. Not a lot of deep bass,

not a lot of extreme treble, but a magnificent

mid-range and more than satisfactory

dynamics. Once you get the mid-range right,

who but lovers of heavy metal and other types

of doof-doof needs ultra-extended bass or

treble?

I say my Leaks were 'near-mint' because the

cambric roll surrounds had hardened with age

over the then 40+ years of their existence. I

took them a speaker repair fellow, based in

Northcote I think, and he recommended

replacing the original sandwich bass drivers

with some hideous, cheap, Chinese rubbish

that had bright yellow cones (but obviously

were not real B&W kevlar units, "copy-cat

yellow" being then the choice of colour for the

cones of nearly all drive units). I recoiled in

horror at the thought, mentally equating it to

the travesty of replacing the 4.2 L straight-six

DOHC XK engine in an E-type Jaguar with a

pushrod Chevy V8 on the grounds that the

latter was more reliable. Barbarian. Instead, in

what can be subsequently described only as a fit

of madness, I sold the amplifier and speakers.

And sold them for a pittance, such stuff being

almost unwanted at the time by audiophiles

who prided themselves on being totally up to

date with all the most modern equipment.

Three words describe that action too: Regret.

Regret. Regret.

Now onto the Williamson amplifier. It has been

described in innumerable reports, of which I

have the published paper by Lankshear (1990),

the magnificent unpublished paper by Stinson

(2020), and the three-part series of books on

valve amplifiers by Popovich (2016). Scott

Frankland wrote a detailed three-piece analysis

in 1996 and 1997 for Stereophile on the history

of push-pull amplifiers and their relation to

earlier, single-ended, typologies. The first of

Frankland's articles (December 1996) described

the historical precedents of the Williamson

design, its dependence upon the earlier (1934)

amplifier design by W.T. Cocking, and how in

turn the Williamson became the basis for much

further development by other audio designers.

The invention of ultralinear operation by David

Hafler and Herbert Kereos in 1951-52 was one

such development.

The Williamson design first appeared in the

April (Part 1) and May (Part 2) editions of

Wireless World in 1947, and was updated in the

August, October and November 1949 editions.

Revisions suggested in the updates included a

change from the original four L63 single triodes

to the use of two 6SN7 dual triodes in the preamp

stage. Interestingly, 6SN7 valves are still

used today (my Cary uses them as phase

splitters). Popovich (2016, p. 190) argued that

"The Williamson's design was not novel even in

its day. There is nothing in it that hadn't been

seen before, except, perhaps, the triode

connection of the [tetrode] output tubes.

However, it combined a few clever design

choices, resulting in a relatively simple yet (for

the time) well performing package." Frankland

(1996, p. 115) was slightly kinder, concluding

that "Williamson's amplifier enjoyed

unprecedented momentum in the marketplace"

and "has become the prototype for feedback

amplifiers the world over." Lankshear

(1990, p. 153) was kinder still, concluding that

"The real importance of Williamson's work

was that he demonstrated that extremely low

distortion was achievable by using plenty of

negative feedback, combined with carefully

designed output transformers. His design set a

standard of performance that is still acceptable

today."

19th Apr 2025

March 2025

JayVee Technologies and HeyNow! HiFi

February 2025

Tim Robbins and Ric Clarke from HRSA

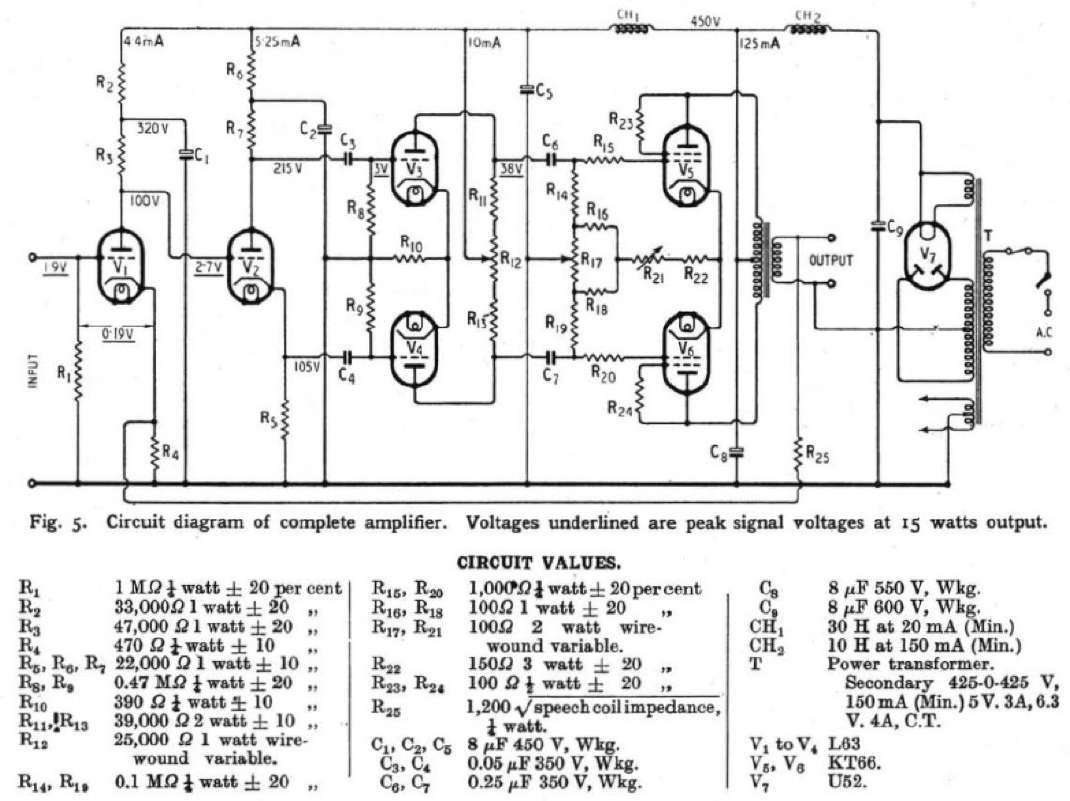

Figure 1 shows the circuit diagram for the early version. You will see the use of L63 triodes in the pre-amplifier stage and two KT66 valves in the output stage. (The KT in the valve's name stands for "kinkless tetrode", the kinkless bit being a reference to the shape of the value's performance curve, representing an effective way to circumvent the similar improvement in response recently patented for pentode valves.) 'The rectifier valve was a U52. In summary, it is a four-stage, Class A triode design using deep global negative feedback (20 dB) and a push-pull typology for the output tubes. The fact it was a four-stage design is important because an additional amplification stage was required to recover the input sensitivity lost due to the use of the global feedback. A push-pull typology using triode valves was considered in the 1940s to be the optimal basis for the design of a high-quality audio amplifier (notwithstanding the triode's chief drawback, high input capacitance).

The Williamson amplifier is significant in audio design, and this is because it eliminated the multiple inter-stage transformers that had been widely used in earlier designs and it DCcoupled the first two stages, both innovations being critical in minimising phase shifts. Williamson recognised it was vital to keep phase shifts to a minimum with a push-pull, negative-feedback design, given that the output transformers were integral to the global negative-feedback loop. The transformers therefore had to be of exceptional quality, otherwise they would be responsible for introducing large shifts in phase at frequency extremes. Were these to develop, what was intended to be a global negative feedback loop would quickly morph into a global positive feedback loop. The amplifier would then become a massive oscillator - with disastrous results for your speakers.

The well-known and respected English transformer maker Partridge Transformers Ltd was responsible for building the output transformers. The primary required 4,400 turns, the windings divided into ten primary and eight secondary sections and as by Lankshear (1990) noted "all interleaved into two balanced halves." They must have cost a fortune to make, and the highlight the deep skill-base of the English audio industry immediately after WW2. Negative feedback was optimised at 20 dB, and levels greater than that, Williamson concluded, served little or no useful purpose.

By demonstrating an Australian-made amplifier of the time that used slightly smaller transformers than those developed by Partridge, Tim and Ric showed just how essential high-quality transformers were to the Williamson design. The single most critical component in any valve amplifier is the output transformer, and as Tim and Ric noted, these are the single biggest cost in a valve amplifier, commonly accounting for at least a third of the total. In this situation there will always be a financial incentive to use cheaper transformers, i.e. ones that are smaller, lighter, less complex, or use lower quality wiring or non-grain-orientated steel in the transformer core. Tim and Ric showed plots of output power and phase shift of the Australian model to show how the amplifier with the smaller transformers had a markedly poorer performance than one with the big, expensive Partridges. It was still a good amp, just not as good as the original design would allow had better (i.e. dearer) transformers been used.

The Williamson amplifier is astonishingly significant in audio history because through it Williamson proposed - and then implemented - a set of design specifications that still hold today. Slightly later than its 1947 debut,

Williamson collaborated with Peter Walker (of QUAD fame) on an article published in a 1952 issue of Wireless World that expanded upon these requirements: Total non-linear distortion (i.e. harmonic and intermodulation) should be less than 0.1% at all power outputs (1-2 % was typical for the time) Linear frequency response within the audible spectrum of 10 Hz to 20 kHz Frequency response should be better than -3 dB at 3 Hz and 60 kHz, in order to minimise phase shifts through the audio bandwidth (40 Hz to 10 kHz + 1 dB was typical at the time) Phase shifts within the entire audio bandwidth should be less than 20o, in order to prevent the amplifier becoming an electronic oscillator Good transient response, with a power supply sufficient to accommodate large dynamic peaks in the music Output impedances as low as possible, and always "much less" than the speaker impedance, in order to provide adequate electric damping and limit undesirable peaks in the bass response of the speaker Hum and noise at least 80 dB below the maximum output. They concluded (p. 357) that this was "a formidable specification, and by no means every amplifier styled as "high quality" will meet it."

Nevertheless, specifications as tight as these were required because of the very great advances in recording quality that had been made in the late 1940s. An example is the introduction in June 1948 by Columbia Records of the 33 1/3 rpm microgroove LP record; until then, far looser specifications for frequency range etc were acceptable as they were sufficient for the shellac 78s and (AM) radio broadcasts that then made up all the program material. Greg Milner, in his 2009 book Perfecting sound forever: the story of recorded music, showed the degree to which recording processes had been improved after WW2 (e.g. as seen in Decca's FFRR records), microphones and speakers had become much better as a result of wartime technical developments in sonar etc, FM radio broadcasts (invented in 1933 but first provided in 1948 in New Jersey), and tape recorders using high-frequency bias (a wartime invention in Nazi Germany by AEG) were just coming onto the market (e.g. the Americanmade Ampex Model 200 in 1948). What an exciting period it must have been for those interested in music reproduction in the late 1940s and early 1950s!

To conclude - we heard last month an amplifier that was designed in 1947, teamed with speakers that first saw the light of day in 1961. In other words, an amplifier from eight decades ago and speakers from six decades ago. What glorious music they made, and made on track after track after track, regardless of genre or period of recording. What perfect, unbridled pleasure they provided. And the track that stood out for me - Elvis' "Can't help falling in love" - was recorded back in 1961 too. In other words, at the same time the Leak speakers were introduced and thus also over six decades ago, recorded using valve microphones and mono valve tape recorders and valve mixing desks etc, etc, etc. Yet we are told relentlessly by audiophile manufacturers that "new is best", that the most recent amplifier and speaker designs are light years ahead of what was claimed as first-class only a few months ago, that only modern 196 kHz 24-bit recordings will do as sources, that we need at least 24, preferably 36, speakers in our living/music/ theatre room to obtain the best sound, and this must include at least six sub-woofers.

Rubbish to all that self-serving baloney. The Williamson amplifier/Leak speaker combination is a superb corrective to the debilitating audiophile disease of upgradism. It makes beautiful music and what our hobby is about is music, not which amplifier has 0.000000001% total harmonic distortion at 2 Hz at a rated output of 3 kW per channel. It provides a remarkable antidote to the Cult of the New. Thus my new credo: "Long live audio 'anachronisms'!"

Further reading:

Frankland, S. (1996). Single-ended vs pushpull. Part 1. Stereophile 19 (12): 110-121.

Lankshear, P. (1990). The Williamson amplifier. Electronics Australia July 1990: 150-153.

Milner, G. (2009). Perfecting sound forever: the story of recorded music. Granta, London. Popovich, I.S. (2016). Audiophile vacuum tube amplifiers. Volume 3. Self-published, Perth.

Stinson, P.R. (2020). The Williamson amplifier of 1947. Available online at: https://dalmura.com.au/static/The%20Williamson%20Amplifier%20History.pdf

Williamson, D.T.N & Walker, P.J. (1952). Amplifiers and superlatives: an examination of American claims for improving linearity and efficiency. Wireless World September 1952: 357-361.

Paul Boon

| January 2025 | Steve Van Sluyter from SpectraFlora |

It was at the 2024 StereoNET Hi-Fi and AV

Show that I met Steve and had the privilege to

listen to his SpectraFlora Celata 88 speakers,

which were enjoyed by myself and many other

discerning punters at the show. As a result, I

was particularly pleased when I learned that

he accepted my invitation to present these

speakers to our club in the Willis Room!

At $35,000 a pair without optional extras such

as stands or special timber, I recognised that

their appeal to the club could be somewhat

limited due to their asking price, but what

makes our General Meetings so great is the

chance to hear some very special equipment

that is potentially far beyond the price range of

our members (myself included), and these

speakers were definitely no exception.

One of the features that Steve was particularly

proud of was the Celata 88's Dynamic

Waveguides, which were specially-optimised

horns designed to combine the benefits of

traditional horn tweeters with those of a

waveguide. I won't go into detail about the

exact technology that went into their

creation. Steve explains it far better than I can

on his newly-revamped website which I'll link

at the bottom of this article.

For the presentation, the Celata 88s were

paired with a Gustard R26 DAC, an Audio

Research Reference 1 preamp and a Parasound

A21 power amp, the same setup with which

Steve normally

showcases his

speakers (including

the StereoNET show).

The results in the

Willis Room, which is

notoriously difficult

for good acoustics,

were nothing short of

spectacular, and many

club members that I

spoke to were also

very impressed with

Steve's presentation.

The carefully-curated

musical playlist for the

evening was also notable, combining classical

pieces from composers such as Bach, Dvooak

and Chopin with a variety of other selections

from artists including Elton John, Ella

Fitzgerald, David Bowie, Pearl Jam and Keith

Jarrett, to name but a few.

Many thanks to Steve and his partner for being

kind enough to travel all the way from

Inverleigh to present to us.

Website: www.spectraflora.com.au

Bailey White

MAC Editor